All Roads Lead to Higher Yields

From Carville to Crisis: Why 1993’s Fiscal Lessons Are Being Ignored

With the Big Beautiful Bill now steadily making its way through Congress — and DOGE disappearing from the front pages — the US fiscal deficit is back as a key market driver.

Moody’s downgrade of US debt wasn’t seismic on its own. But it did refocus investor attention on the budget arithmetic. And the numbers are getting harder to ignore.

Whether we’re on the cusp of a debt crisis is hard to call. But the broader outlook is becoming clearer — and more worrying.

Trump 2.0 is shaping up just like Trump 1.0: ever-widening deficits and rising debt. The goal of hitting a 3% deficit under Scott Bessent’s 3/3/3 plan now looks far-fetched.

The CBO estimates the new bill will add $3.8 trillion to the deficit over the next decade. Even before this, they projected debt-to-GDP rising from 100% to 118% — and that assumed 10-year yields stay under 4%. That already looks optimistic.

Some in the market are starting to ask: could the US face its own “Liz Truss moment” — a disorderly bond market sell-off?

The comparison is only partial. In the UK, it was forced selling of Gilts to meet pension LDI liquidity needs that really accelerated the Gilt sell-off.

But the bigger question is this: are we nearing the tipping point of fiscal dominance — where bond markets, not policymakers, start setting the agenda? And will it take a meltdown to force Washington into making the hard fiscal choices it’s been avoiding?

Back to 1993

The year was 1993, when James Carville, political advisor to Bill Clinton uttered his oft-repeated remark

“I used to think that if there was reincarnation, I wanted to come back as the president or the pope or as a .400 baseball hitter. But now I would like to come back as the bond market. You can intimidate everybody.”

US 10-year yields were just over 6% and with inflation running at about 3%, real yields at over 3% were seen as an impediment to growth. The economy was recovering from the 1990-1991 recession, but recovery was slow. It was called the jobless recovery. The unemployment rate was still above 7.0%, having peaked at 7.8% in July 1992.

The fiscal deficit was close to 4.5% of GDP, perhaps not unsurprising given the weakness of the economy, but touching the highest levels in about a decade. Clinton understood that to stimulate growth he needed to get interest rates down. Encouraged by Fed Chair Alan Greenspan, he knew a fiscal adjustment would make it easier for the Fed to pursue easier monetary policy.

He raised the top rate of income tax from 31% to just under 40% in the Tax Reform Act of 1993. Although the Fed raised interest rates in 1994, they cut in 1995, and long-term yields trended lower through much of the mid-late 1990s, contributing to the virtuous cycle of rising asset prices and strong economic growth.

Of course, Greenspan’s new paradigm economy was also a factor, as was the global disinflationary trend underway after the fall of the Berlin wall in 1989. But the change in the fiscal picture was real. In fact, by 2000 the US posted a fiscal surplus and the chat in the Treasury market was whether the government should stop issuing long bonds.

Modern Monetary Madness

But that was the turning point. The post dotcom bust saw the deficit rise as the economy went into recession and the George W. Bush tax cuts further increased it. After the Global Financial Crisis, the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, combined with the TARP, saw the deficit rise to almost 10% in 2009. But the Zeitgeist still called for austerity and in the subsequent years the deficit fell back to more normal levels by the mid-2010s.

While 2000 may have been the turning point, 2017 was the tipping point of legitimising large deficits. Despite the unemployment rate being only 4%, a significant tax cut was deemed necessary. By the end of 2019, the deficit had grown to 4.5%, about the same level facing Clinton in 1993, but this time for an economy at full employment.

COVID cemented the structural shift providing a justification for an eye-watering deficit of 15% in 2020. But unlike the post-GFC era, when the virus departed, there was no appetite for fiscal consolidation. Instead, Modern Monetary Theory was the new dogma.

In the aftermath of COVID and Russia’s advance on Ukraine, Bidenomics brought the justification of national security threats, potential supply chain disruptions and the need to rebuild flailing US infrastructure to the Chips Act and Inflation Reduction Acts. It was the end of the neoliberal era of free markets and conservative fiscal policy.

The inverse relationship between unemployment and the deficit was still in place, but the curve had shifted — deficits were now significantly larger at every level of unemployment than they were in the past.

The Trend Change in Bond Yields

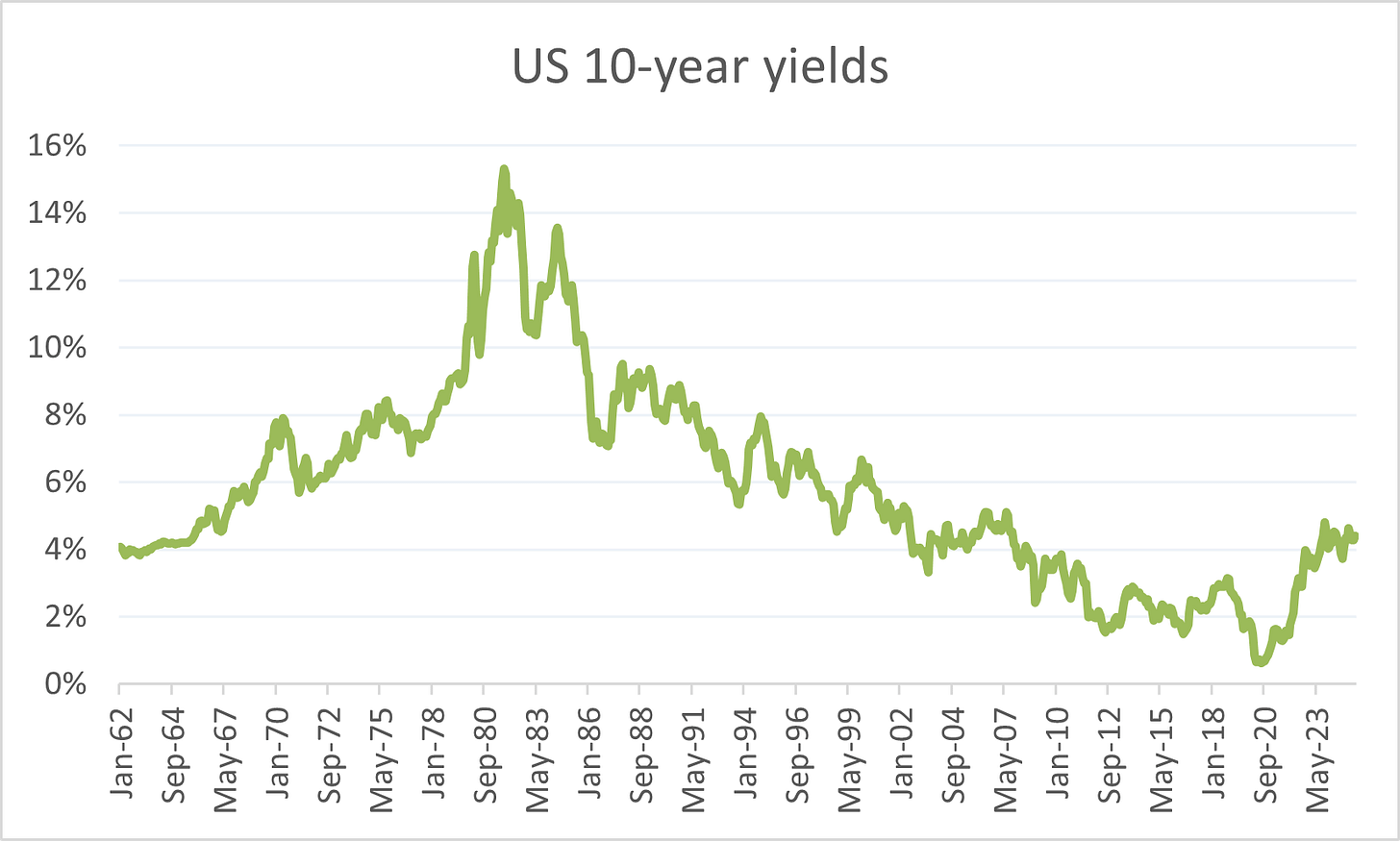

While the initial impulse of COVID was deflationary, with bond yields falling to historic lows in March 2020, the bond market eventually took note of the radical shift in policy that was underway.

The underlying driver of bond yields is the balance between savings and investment, and that balance was tilting to higher investment spending.

The era of secular stagnation of the 2010s saw excess savings and weak investment demand forcing yields down, but that changed with the large fiscal deficits of the COVID years and the growing need for investment in defence and other projects in subsequent years.

It’s no coincidence that after the Democrats won the runoff elections in Georgia in January 2021, giving them effective control of the Senate, bond yields started to rise in anticipation of higher spending. Yields have trended higher ever since.

Other factors have accentuated the move. Inflation has shifted into a higher range meaning investors require a higher yield in nominal bonds and central banks have ceased asset purchase programs and have turned net sellers of bonds.

Some Unpleasant Fiscal Arithmetic

The trouble with a structural rise in yields is simple: higher yields raise the cost of issuing new debt, and old debt gets refinanced at higher rates.

In theory, a country that borrows in its own currency can't default. But if investors lose faith in the fiscal trajectory, they’ll demand a much higher risk premium to hold Treasuries. That’s when debt sustainability becomes a real concern.

That’s where the U.S. finds itself today — caught between rising costs and fading confidence.

At the heart of any debt sustainability analysis is the relationship between interest rates and growth: R – G.

If nominal GDP growth exceeds nominal bond yields (G>R), growth is sufficient to generate the tax revenues to service interest rate costs. But, if R>G the arithmetic changes and an increasing amount of tax revenues goes on servicing debt.

Let’s say inflation settles at 2% or even 2.5% and real GDP growth is a respectable 2%, nominal GDP growth is 4-4.5%. But US 10-year yields are already at about 4.5%. That’s why a move above 5% would be so worrisome.

As every emerging market knows, once investor confidence goes, yields jump. The result: a vicious cycle of rising interest costs, wider deficits, and even greater risk premiums.

Can Growth or Inflation Save Us?

Of course there are solutions to the problem. Stronger economic growth would generate higher tax revenues and arithmetically would reduce the debt as a percentage of GDP.

Optimists point to AI as a potential saviour in that regard. Couldn’t an AI fuelled productivity boost, just like in Greenspan’s New Paradigm Economy propel the economy to a higher growth rate, keeping the deficit in check?

It’s possible, but the potential impact of AI on the economy is fiendishly difficult to assess never mind quantify. And even if AI transforms the economy, the experience of the internet would suggest a large lag between the development of the technology and the realisation of productivity gains.

And what about higher inflation? Can’t we just inflate our way out of the debt?

Yes, higher inflation does erode the real value of debt, and the US got the benefit of this with the inflationary surge of 2021. But the problem with this is market expectations quickly adjust and if inflation is seen as endemic, investors require compensation in the form of a higher inflation risk premium in bond yields.

Making some tough choices on spending and cutting the deficit is a third solution. But such changes were politically challenging even when there was a semblance of bipartisanship in Congress. It is hard to envisage agreement on major spending cuts at the current juncture.

The Coming Era of Fiscal Dominance and Financial Repression

The warning sound now is that we may now be approaching the point of fiscal dominance. It’s the moment where monetary policy is directed at managing the sustainability of fiscal policy.

It could mean the Fed keeping interest rates lower than otherwise to keep down debt servicing costs, or it could mean a return to QE and outright purchases of treasuries to keep long-term yields under control. In either case monetary policy is directed at debt sustainability in the first instance rather than price stability.

Could that really happen in the US?

Going back in history it has. The Fed engaged in yield curve control in the 1940s to keep borrowing costs under control during World War II. That only ended in 1951 after the Fed and the Treasury had a standoff and the Fed eventually reasserted its independence via the Treasury-Fed Accord.

But it could come in another variant, via moral suasion or arm twisting the Fed. In the 1970s, Nixon bullied Fed Chair Arthur Burns and planted stories in the press about him seeking a pay rise to discredit him and force him into easier policy. The result was a decade characterised by a trend drift higher in inflation.

Back to the Future

In 1993, the debt/GDP level was only 47% and the deficit was only 4.4%, yet Clinton saw the need for a fiscal adjustment — and had the political capital and congressional alignment to deliver it. The result was a win-win of fiscal adjustment, lower yields and stronger growth.

Today, the US debt/GDP is more than double what it was then, and the deficit is 50% higher, yet the ideological and political consensus does not exist to address them. The era of low interest rates has allowed a complacency with respect to deficit spending to take hold just as the challenge of addressing entitlement spending looms large.

Now, not only are debt and deficit levels higher but the debt sustainability dynamics of R versus G are deteriorating as well. Only a market-induced crisis will force action.

How things play out from here is anybody’s guess but here are three possible scenarios:

(1) Bond yields remain elevated, but assuming a 10% baseline tariff is eventually pushed through (with higher tariff on certain target industries) the impact on growth will become more apparent as we go through the year, pushing the US economy into recession and allowing the Fed to ease. That would take the heat out of longer-term yields even allowing for a likely steepening of the yield curve. In the short-term a crisis would be avoided but the deficit would likely grow even bigger in the downturn and the trend higher in rates would resume next year when the economy recovers.

(2) Growth remains resilient while inflation responds to the impact of tariffs forcing the Fed to shock the market with higher, not lower, rates this year. Bond yields spike and strains between the White House and the Fed ramp up. Yields might accelerate as a sustained break of 5.0% on the 10-year yield could force unforeseen consequences such as on bank balance sheets or unearth other vulnerabilities in the system. We could see a quick move to 6% and a significant sell-off in equities. The equity sell-off and higher yields would probably cause a recession and ultimately see yields peak for the cycle, but the underlying vulnerability would remain.

(3) The economy slows and the bond markets stays in a broad range. The Fed doesn’t hike but it is slow to ease. By next year, it will be time for Trump to replace Powell and he does so with a more sympathetic Fed Chair. Although the other voting members of the FOMC still exert restraint, having a Fed leadership with more dovish leanings produces a Fed inclined to tolerate higher inflation. The market sees this and demands a higher inflation premium, particularly as the US dollar weakens in response to a perception of reduced credibility. Growth holds up but bond yields trend higher and we enter the era of financial repression whereby the government is forced to use moral suasion and other measures to force domestic investors to buy Treasuries.

As Paul Tudor Jones remarked last year, “all roads lead to inflation” and that has obvious implications for the bond market.

When I started working in the markets in the mid-1990s, traders used to remark about the JGB market that it was the sell of the century. The question was which century!

As Rudi Dornbusch once quipped, “a crisis takes longer to develop than you think, and then evolves more quickly than you thought possible.”

Fiscal risks are mounting in the Treasury market. Whether it’s this year, next year, or beyond — all roads lead to higher yields.

Thank you, Alan, for this insightful and thought-provoking article. Without meaningful fiscal consolidation, easier monetary policy risks exacerbating stagnation rather than fostering sustainable growth

This is a great “vista" onto the dilemma we are facing, and I like the great quotes you braided into this piece.

We are looking at the prelude of the upcoming big clash between government(s) and central bank(s). Russell Napier just called his latest piece "The Anguish of Central Banking 2" (after what happened in the 1970s).

He quotes Arthur Burns after he had left the Fed (speech in Belgrade, 1979):

"… And yet, despite their antipathy to inflation and the powerful weapons they could wield against it, central bankers have failed so utterly in this mission in recent years. In this paradox lies the anguish of central banking."